As a chess team captain at the University of Chicago in 1968, Harold Winston won a decisive match that clinched the national and Pan-American championship. Among his college chess rivals was George R.R. Martin, the future “Game of Thrones” author who wrote of a certain archrival in his short story “Unsound Variations.”

Martin “put him in a story as ‘Hal Winslow,’” said Mr. Winston’s wife, Dr. Carol Weinberg.

Winslow was the rumpled, clipboard-carrying U. of C. chess team captain in “Unsound Variations” who also shares Mr. Winston’s initials.

“It was never easy between U. of C. and Northwestern,” a character in the Martin story says. “All through my college years, we were the two big Midwestern chess powers, and we were archrivals. The Chicago captain, Hal Winslow, became a good friend of mine, but I gave him a lot of headaches.”

A representative of Martin said the author was unavailable.

“They played chess together in the college leagues, and you read the passage, and you know it’s Harold — with the clipboard, a little bit disheveled,” said Al Lawrence, managing director of the U.S. Chess Trust charity. “There’s too many hints to deny.”

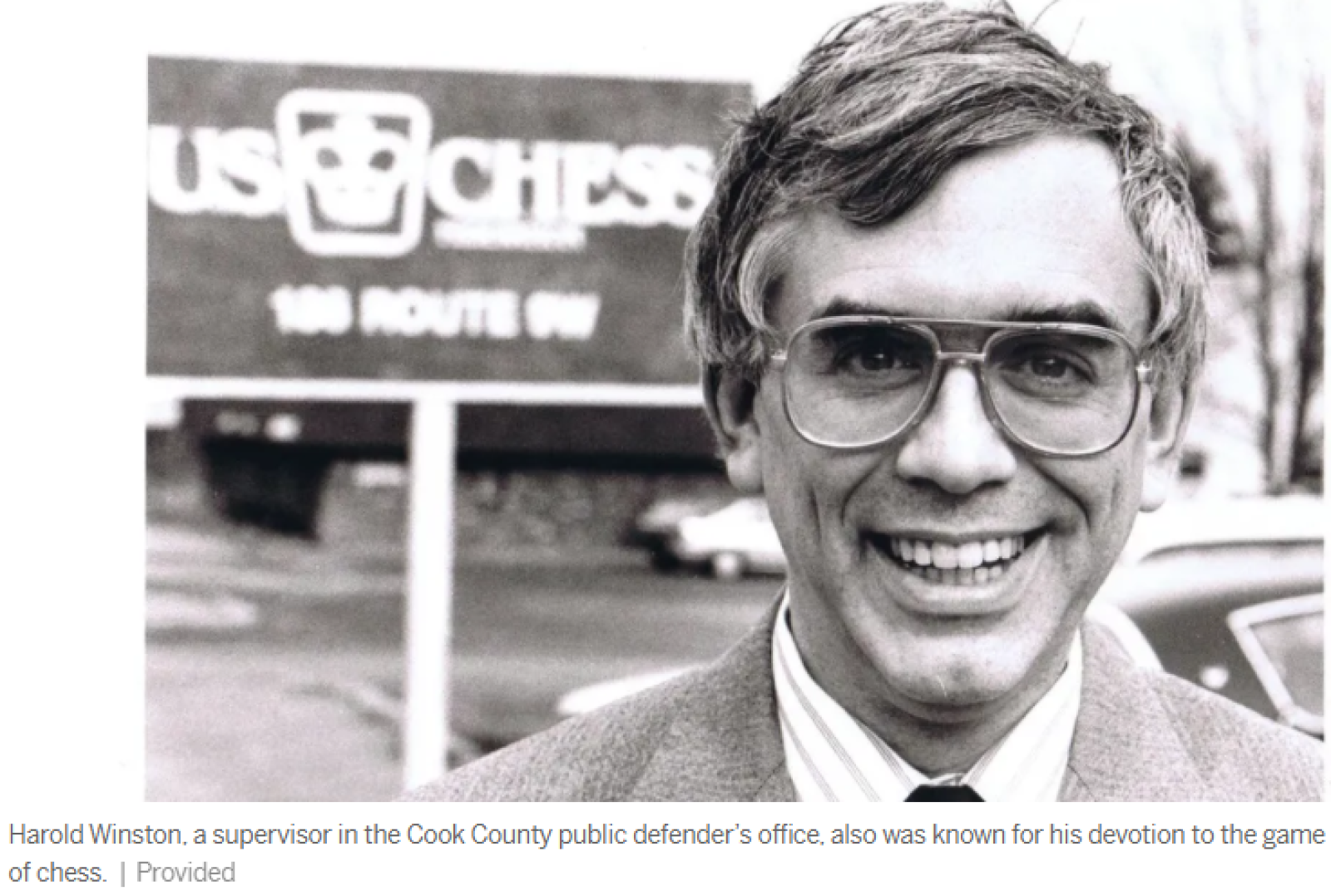

Mr. Winston, who chaired the U.S. Chess Trust and was a supervisor in the Cook County public defender’s office, died of heart failure in February at 75. He was a Naperville resident.

From 1987 to 1990, he was president of the trust’s parent organization, the U.S. Chess Federation, the governing body for chess in America.

Mr. Winston put his knowledge of openings, gambits and endgames to use while fighting to overturn convictions and win new trials for defendants as a supervisor in the public defender’s office, where he worked since 1991.

“He knew both strategy and tactics,” said Robert C. Drizin, an assistant public defender. “I referred to him as the grandmaster of post-convictions — like a chess player who’s always thinking of moves ahead.”

“Harold was a giant in chess,” Lawrence said. “Many of those in our realm of 64 squares and a ticking clock — where the debates only seem like life and death — had little knowledge of Harold’s prominence in the world of real life-and-death arguments. He won new trials for people convicted of murder in at least seven separate cases.”

Mr. Winston helped free Alton Logan, who spent more than 25 years in jail for the 1982 killing of a security guard — a crime he didn’t commit.

Another man, Andrew Wilson, admitted to his attorneys that he’d been involved in the killing, but Wilson’s lawyers said they couldn’t share the admission because of attorney-client privilege.

It wasn’t until the 2007 death of Wilson — who’d been convicted in the killings of Chicago police officers William Fahey and Richard O’Brien — that his lawyers came forward, with Wilson’s approval, to share his confession.

At one point, he also represented serial killer John Wayne Gacy when he was on Death Row.

“He was a unique individual,” his wife said, “because many people of his intellect and ability would be in law for the money, and he was in law for the service.

“He really did try to make the world a better place,” she said.

Growing up in the Bronx, young Harold loved games of strategy like Risk and Monopoly. Playing Clue, he’d solve the murders before anyone else, according to his brother Marvin Winston, who said, “He was like a Sherlock Holmes.”

He played on chess teams at the Bronx High School of Science and the City College of New York. After studying history at U. of C., he got his law degree from Loyola University Chicago.

Mr. Winston worked to distribute chess sets inside of prisons, tried to keep the price of chess conferences low enough so players on budgets could attend and ran tournaments for women.

“He understood that chess could help everyone and should be open to everyone,” Lawrence said, “whether it was African American players, women players, players with disabilities, junior players, incarcerated players.”

In chess, Mr. Winston earned the official designation of “expert” — the ranking just below “master.” That placed him above 99% of tournament players in the United States, Lawrence said.

He enjoyed a Christmas Eve tradition known as “simuls” — playng simultaneous chess matches. At the invitation of an Oak Park rabbi, he’d play a dozen or more games at the same time, moving from table to table to play members of his congregation.

He loved travel, often stopping to see Civil War battlefields while en route to and from chess events.

Mr. Winston is also survived by his daughters Elizabeth and Katherine Winston. Services have been held.