Corzell Cole is working on his redemption story.

During the 17 years he’s been behind bars, Cole has actively tried to make positive change for his community, his family and himself.

“The reality is that I wake up in prison every day, but that doesn’t mean I don’t have goals,” he says.

Cole is a 36-year-old man with a gregarious demeanor and perfectly maintained hair that he learned to trim while working at his cousin’s barbershop in Joliet, Ill. In conversation, he’ll take any opportunity to bring up his kids — three sons who are 21, 20 and 17 years old.

“I’m parenting from the penitentiary,” says Cole. “My father wasn’t around when I was growing up, and I want to make sure that my sons won’t make the same mistakes I made.”

When Cole was 19, he was arrested on first-degree murder and attempted murder charges for his role as the driver in a shooting that killed a man and injured his teenage daughter. Cole was convicted and sentenced to 50 years in prison. He is contesting the conviction.

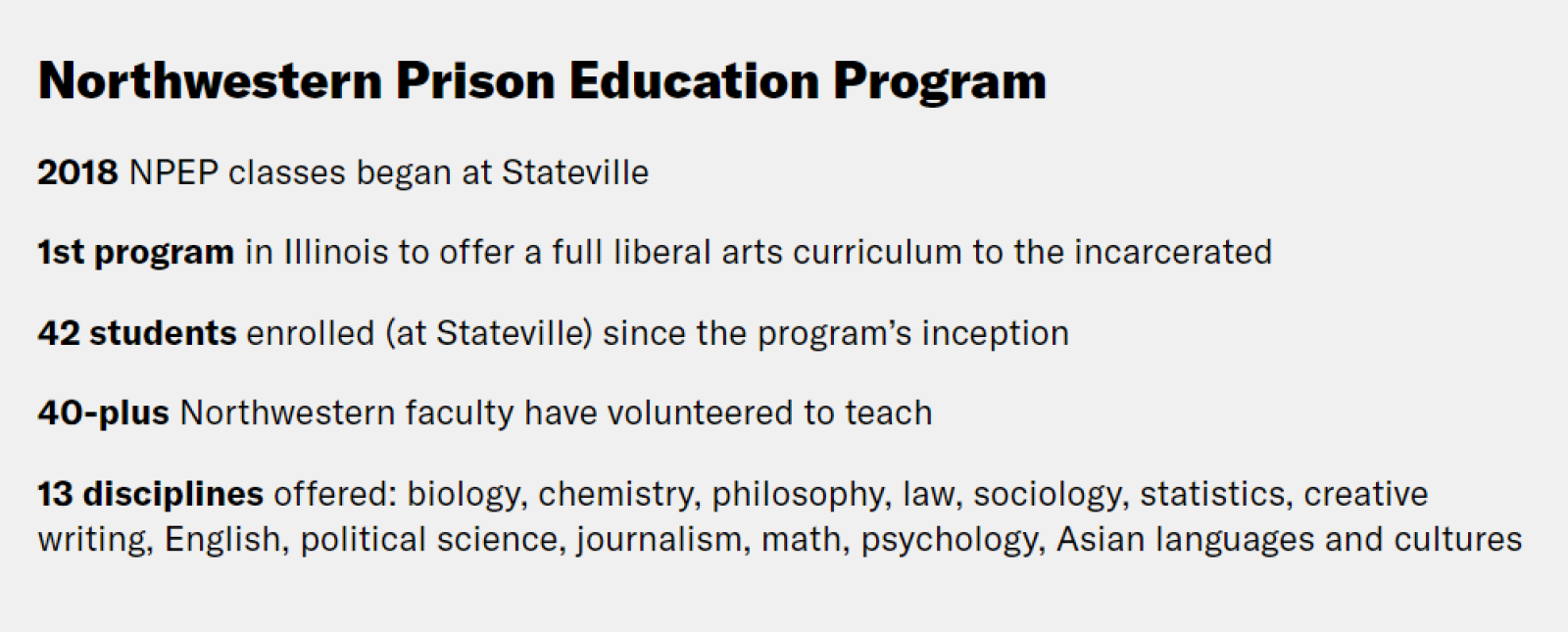

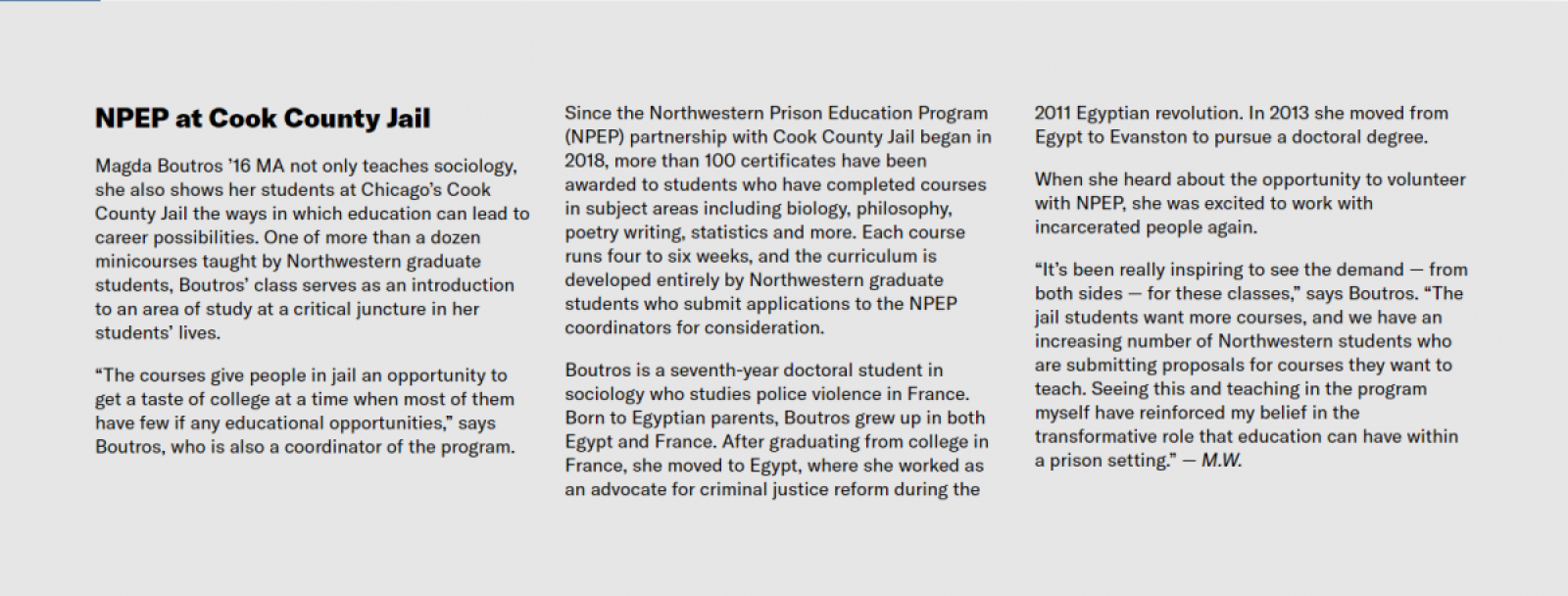

Almost two decades later, Cole is one of 42 men enrolled in the Northwestern Prison Education Program (NPEP) inside Stateville Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison for men in Crest Hill, Ill., located about an hour southwest of Chicago.

NPEP is a partnership between Northwestern and the Illinois Department of Corrections that grants college credit through the University’s School of Professional Studies and in collaboration with Oakton Community College. Upon fulfillment of course requirements, NPEP students are eligible to earn an associate degree in general studies from Oakton. The program, founded and directed by Northwestern philosophy professor Jennifer Lackey, is the first in the state to offer a full liberal arts curriculum.

“The men in this program are phenomenal writers, they’re aspiring lawyers, and they want to start businesses to promote economic development in their home communities,” says Lackey, the Wayne and Elizabeth Jones Professor of Philosophy in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences. “They’re the same kinds of intellectually curious students we admit to Northwestern every year.”

Northwestern volunteers, both faculty and students, play a vital role in every aspect of NPEP. At Stateville, Northwestern faculty teach in the program, and doctoral students also design and teach courses, while undergraduates serve as peer tutors at weekly study halls. On the Evanston campus, students organize extracurricular workshops and guest lectures to take place in the prison, raise funds for classroom supplies for Stateville students and run NPEP’s social media channels.

“Hearing from our professors, students and volunteers, it’s clear that NPEP has had a positive impact on the entire Northwestern community,” says Lackey.

Lackey has cared about prison populations since she was 12 years old. To fulfill a community service requirement for school, she asked to volunteer at Cook County Jail. Once her request was approved, Lackey spent time visiting with women at the jail and hearing their stories.

“I was raised by a single mother and I recognized — even as a child — just how many people end up incarcerated in this country due to circumstances outside of their control, and how incarceration can upend their entire lives,” says Lackey.

The U.S. has the highest number of incarcerated people — roughly 2.2 million — of any country in the world, with incarceration rates four to eight times higher than other democracies. Additionally, a recent study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics showed that 77% of people released from state prisons return within five years.

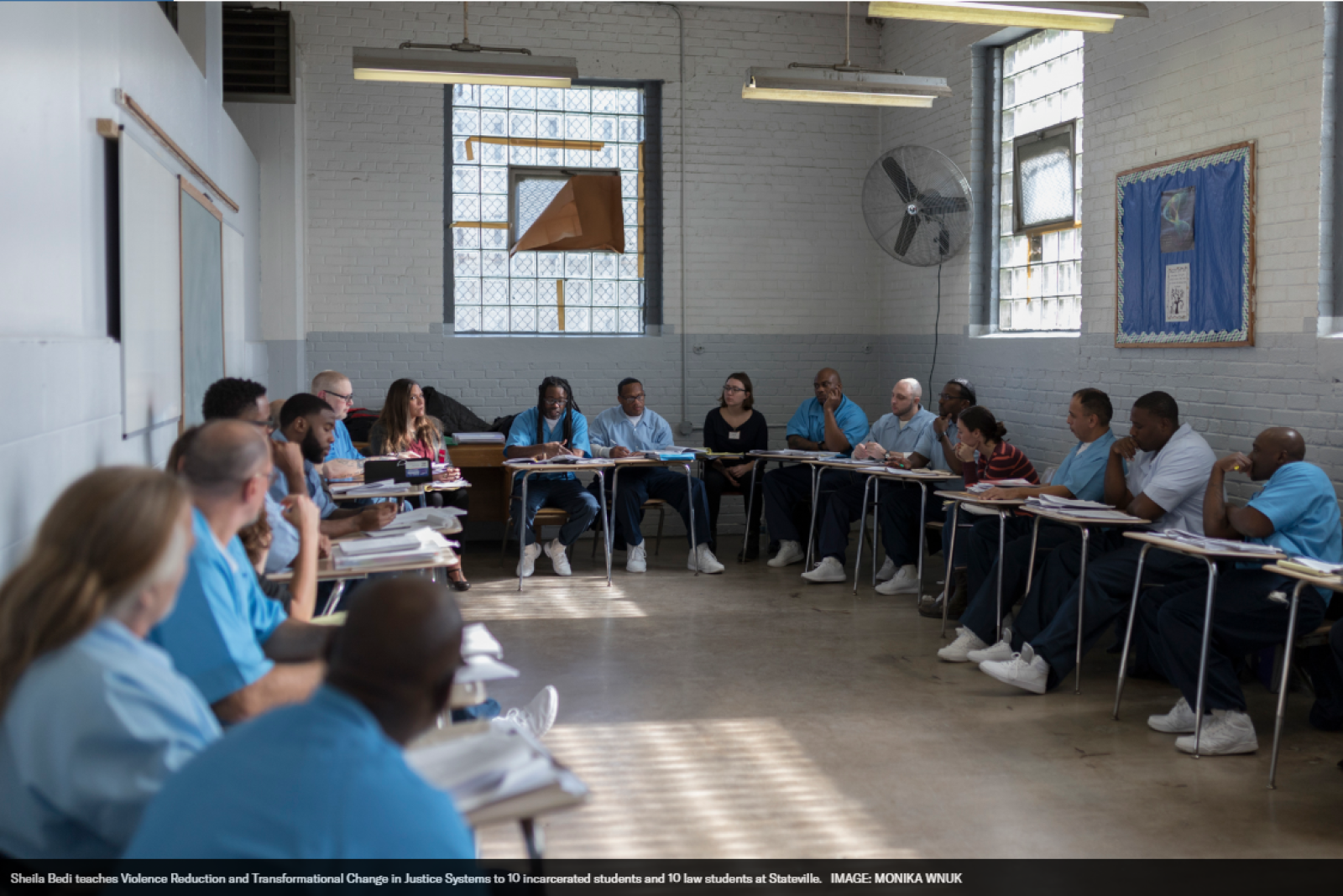

Civil rights attorney Sheila Bedi has dedicated her career to ending mass incarceration. “The men at Stateville — and many men and women who are imprisoned in this country — have experienced systemic state disinvestment in their home communities, as well as the realities of mass incarceration and overpolicing,” says Bedi, a clinical professor at Northwestern Pritzker School of Law. At Stateville she teaches Violence Reduction and Transformational Change in Justice Systems to a class made up of 10 incarcerated students and 10 law students.

One of her incarcerated students is William Peeples. At 55, Peeples is among the oldest students enrolled in the course and has spent almost all of his adult life in prison.

“The first time I went to prison was for something I wasn’t guilty of,” says Peeples. “I was 18 and thrown into a predatory environment, surrounded by hardened criminals. It didn’t give me much faith in the judicial system.”

While Peeples is grateful to learn more about the law himself — Stateville inmates are often well-versed in the legal details surrounding their cases — he also sees his involvement in NPEP as an opportunity to make a difference in the lives of others navigating the legal system.

“The opportunity to share my perspective with these young lawyers who are going to be defense attorneys, state’s attorneys and judges who might even end up on the U.S. Supreme Court is invaluable and could really make a difference,” says Peeples. (Read his essay, “When You Know Better, You Do Better.”)

The discourse between the two populations was a big reason that Bedi decided on the 50-50 format enrollment for her class at Stateville.

Luke Fernbach, a second-year law student in class with Peeples is interested in civil rights law and prison reform. After graduation he hopes to pursue work that helps shrink the role of policing and reduce the number of people in prison by building up communities and promoting crisis intervention efforts — the types of efforts that might have helped some of his incarcerated classmates avoid prison. “One of the most important and often overlooked things you should learn as a lawyer is that in a lot of cases, the people who have the best solutions to legal questions are those most affected by them,” says Fernbach.

Research has shown the numerous benefits of prison education. A large 2013 study by the Rand Corp. found that participation in a prison education program reduces re-arrests by 43%. The chance of re-offending also falls dramatically depending on the level of education completed. Furthermore, for every $1 spent on prison education, $4 to $5 is saved through reduced recidivism.

“I’m always surprised when people say we don’t know how to deal with violence, because we absolutely do,” says Lackey. “Education has been shown time and time again to be the most effective way of positively intervening in the criminal justice system.”

The relationship between prison education and recidivism makes a strong case for Rob Jeffreys’ agenda since he became acting director of the Illinois Department of Corrections last June.

“We have to be taking all the necessary steps to reduce recidivism and make people better when they leave than when they came in,” he says. Jeffreys was appointed to the role by Gov. J.B. Pritzker ’93 JD after 21 years with the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections. Since he took office, Jeffreys has hired staff to lead efforts that bring technology — including internet access — to Illinois prisons, coordinate prison volunteer programs and provide re-entry services.

Even with strong data to support it, prison education has not bounced back since the Crime Bill of 1994, through which Congress cut access to Federal Pell Grants — need-based grants for low-income undergraduate students — for prisoners, reducing the number of college-degree programs in prisons nationwide from 350 to just 12 by 2005. In 2015 the Obama administration approved a pilot program reinstating Pell Grant access to a portion of the incarcerated population — about 12,000 people to date — a first step toward incentivizing program development. In April 2019 a bipartisan bill was introduced in Congress to fully reinstate Pell Grant access for incarcerated people.

Still, programs like NPEP require investment from academic institutions and donors to exist. Recently NPEP was awarded a $1 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. In addition to supporting the NPEP program at Stateville, the grant will make it possible for Lackey to begin work on the only postsecondary prison education program for women in Illinois, at Logan Correctional Center in Lincoln — fulfilling her dream to help women like those she met on that first service trip years ago.

Mary Pattillo didn’t know how a reading about foie gras would go over with her Stateville students. Teaching the same first-year sociology course at Stateville and in Evanston meant that she used the same syllabus for both cohorts, with identical readings and writing assignments. One of the readings was about the 2006 foie gras ban approved by the Chicago City Council after members decided it was inhumane to force-feed the birds.

“Very few students — whether from Evanston or Stateville — knew that foie gras is duck or goose liver,” says Pattillo, the Harold Washington Professor of Sociology and African American Studies. “But we had the most fascinating discussion about the limits of government control, and the Stateville students chimed in about their own lack of control over their meals in prison.”

This was not the first or last time that discussion topics produced different responses on both campuses. The class, which examines Chicago using sociological methods, included readings about various neighborhoods known for cultural diversity. While Pattillo’s Evanston students were from all over the country, her Stateville students — many of whom grew up in the Chicago area — knew the city. They were also much older than the Evanston undergraduates. Some had children who were about the same age as their Evanston peers.

“Where Evanston students were green to sociology and to Chicago, the Stateville men knew Chicago and brought their experiences to class,” says Pattillo, who is one of more than 40 Northwestern professors signed up to teach in the program. “What they didn’t have was up-to-date information about the city, and because they were without internet access, I often had to go to the library and pull articles they requested for their research papers.”

Corzell Cole is one of the students who took Pattillo’s course. Cole grew up just a few minutes from Stateville, in neighboring Joliet, and recounts an early exposure to drug deals and shootings. When he was 8, Cole was hit in the arm by a stray bullet that ricocheted through his body, causing his lungs to collapse.

“That injury was a major setback for me — in sports and in school,” says Cole.

He remembers taking care of his brother, while their mother worked two, sometimes three, jobs to support the family. Cole’s father, who had battled addiction after losing a steady job, didn’t play a consistent role in his life.

“Taking Professor Pattillo’s sociology class allowed me to gain a deeper understanding of my own story,” says Cole. “I was able to put my life into the context of systemic issues that happen in impoverished neighborhoods. My father losing his job, my parents separating and my mother raising two boys on her own — those things contributed to how I ended up in this situation.”

Pattillo, whose research bridges sociology and African American history, has written about incarceration and has family and friends who have been incarcerated.

“People who are in prison are probably the absolute last constituency that even the champions of education would champion,” she says. “What I have seen firsthand is just how much talent is locked up for life. I would argue that using your mind, your body and your spirit — which is what learning is to me — is humanity 101.”

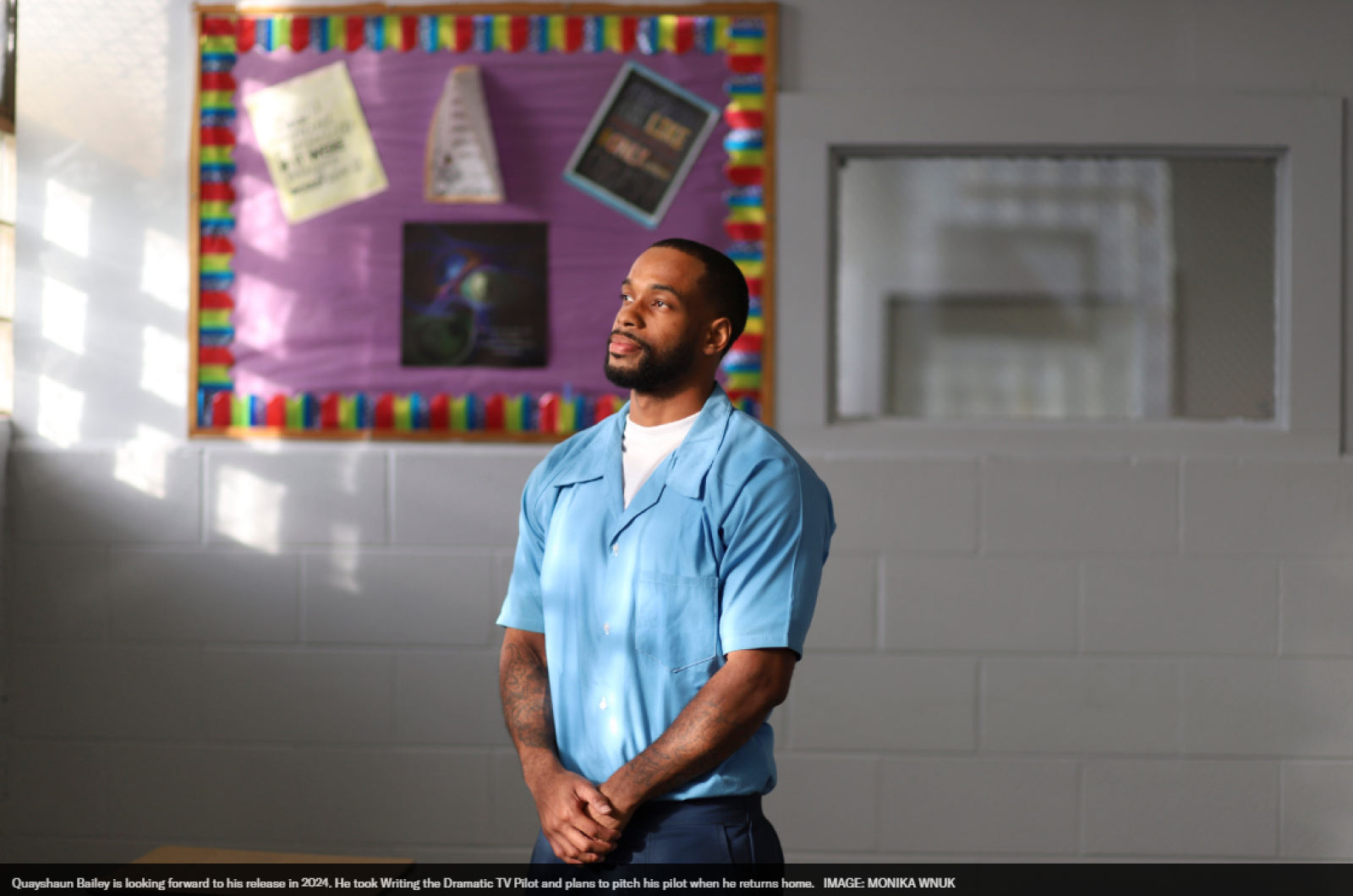

While many of the students are enrolled in core subjects including sociology, chemistry and math, there is room for electives as well. Quayshaun Bailey opted to take Writing the Dramatic Television Pilot.

“The assignment said we were supposed to write 15 pages, but I wrote the whole 60 required for a one-hour pilot,” says Bailey, who wrote a script for a crime drama. “If I get some good feedback from that, I’m going to tuck

it away and see if I can pitch it when I’m out.”

Bailey, 27, has five years left in his sentence. He is one of a few students who transferred to Stateville from a medium-security prison after he was admitted to NPEP.

“I’ve been pursuing an education since I was first incarcerated, but when I heard about this opportunity with Northwestern, I saw the chance for my potential to skyrocket,” he says.

The class Bailey took was taught by playwright Brett Neveu, who teaches in Northwestern’s School of Communication. Neveu remembers his father volunteering at the prison in their hometown of Newton, Iowa.

“My father taught me that giving time could be just as valuable as giving money,” says Neveu.

Neveu’s course challenged students to learn the technical framework of TV pilot writing, starting with story mapping, and then to write their own pilot. As inspiration, he assigned readings of the pilot scripts of popular dramas including Mad Men, Friday Night Lights and The Crown. He was also able to get a gate pass approved for audiovisual equipment so that the students could watch the pilot for Lost. Neveu asked students to pay special attention to how the writer established tone and led the audience to want to watch the second episode.

“We talked a lot about the importance of voice in the television industry,” says Neveu. “Reading the students’ pilots, their voices — and the voices from their neighborhoods — came across loud and clear. It made me realize that voices like theirs are missing in writers’ rooms today. We need their voices on television.”

Stateville students have had their work picked up by prominent outlets before. In 2016 Alex Kotlowitz, author and journalism senior lecturer and writer-in-residence at Northwestern's Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications, helped eight inmates write personal essays that were published on the New Yorker’s website and became the basis for “Written Inside,” a podcast produced by WBEZ, Chicago’s NPR affiliate. This winter Kotlowitz, a two-time recipient of the Peabody Award for journalism, returned to Stateville to teach Criminal Justice Reporting: A Class Taught Inside to 10 Stateville students and 10 Northwestern journalism undergraduates.

Many opportunities that are common on college campuses — like hearing prominent guest speakers, enrolling in workshops or assuming leadership roles in student organizations — can be difficult to replicate in a prison.

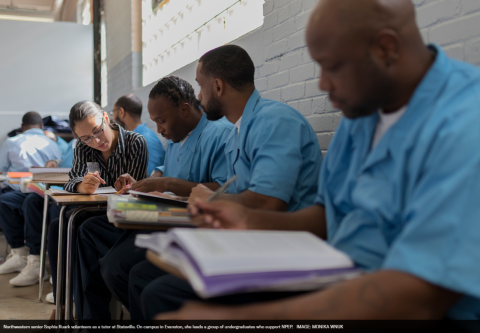

That’s where Sophia Ruark comes in. As president of the Undergraduate Prison Education Partnership (UPEP), an army of Northwestern students behind the scenes who support NPEP, Ruark leads a group of students developing extracurricular programming, fundraising for academic supplies and building awareness of NPEP on the Evanston campus.

In 2019 UPEP organized a Buddhist psychology and meditation workshop at Stateville, which included Stateville and Evanston students.

“So many students came up to me after class to tell me how meaningful it was to have that space to share candid, emotional topics and learn how to use meditation,” says Ruark, who is a senior pursuing a psychology major and legal studies minor. “In all the ways we would help Evanston students be successful, we should help the Stateville students too.”

Ruark, who is from Grand Ledge, Mich., stepped into an adult role after her father became incarcerated while she was in high school. At the time, she wasn’t sure if attending college would allow her to support her family. Interested in a future career in the U.S. Air Force, Ruark applied and was accepted to the Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps, a program that allows students to complete officer training while getting a college degree. Now she says that her decision to support NPEP provided a way to bridge two important parts of her identity — student and servicewoman.

“The Air Force teaches you that you have a responsibility to your unit,” says Ruark. “NPEP — my peers at Stateville and in Evanston, everyone who works so hard to make NPEP work — became my unit at Northwestern.”

This spring Ruark, who received a Purple Pride Award at the 2019 Wildcat Excellence Awards for her work with UPEP, will graduate from Northwestern and become an officer in the Air Force. In the fall she will commission and begin serving as an aviator, becoming the first woman in her detachment in at least five years to do so.

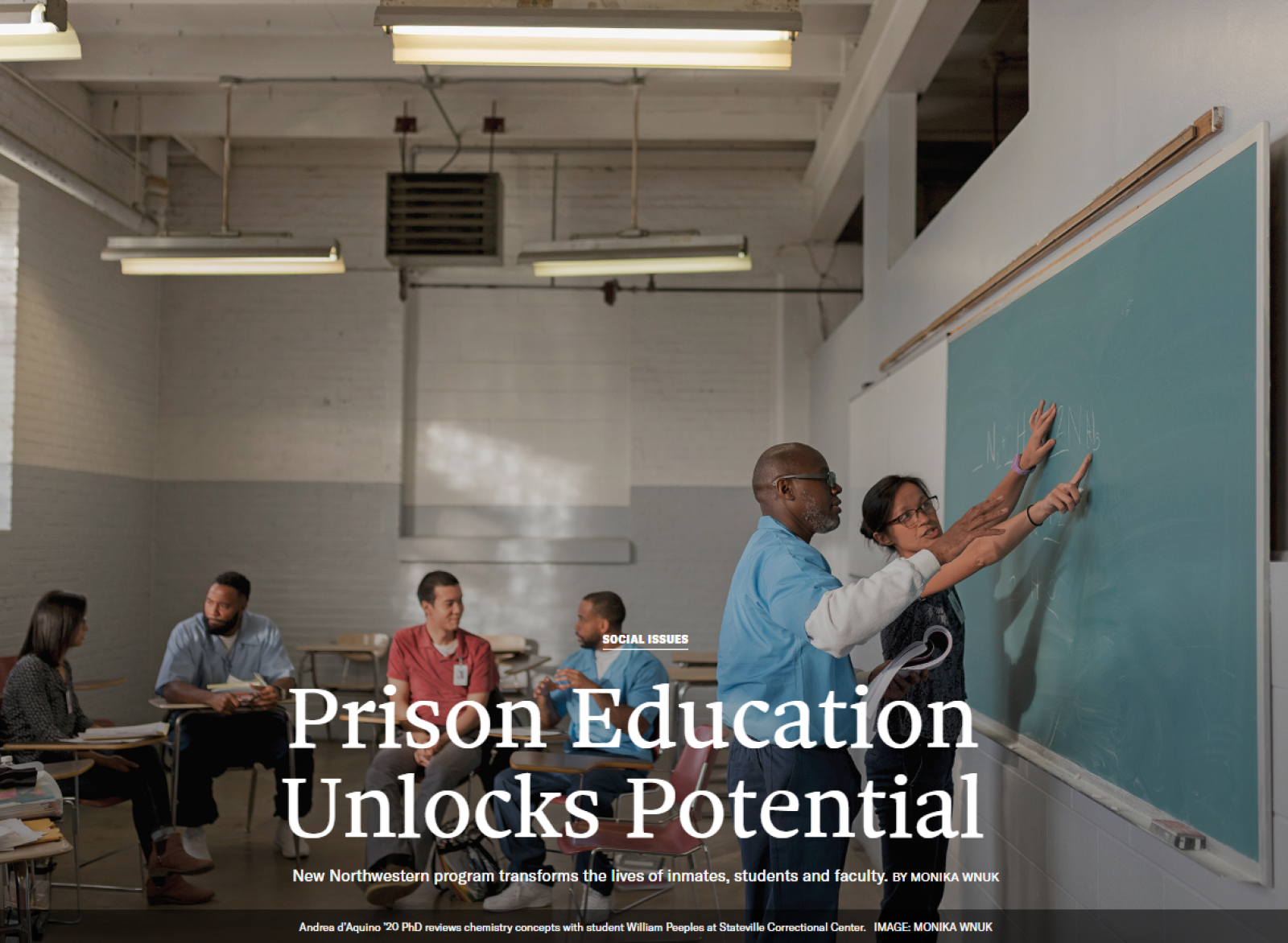

NPEP tends to attract high-achieving Northwestern students like Ruark. On a Thursday night last fall, Andrea d’Aquino ’20 PhD defended her doctoral thesis in front of the chemistry department, her friends and her family — including her identical twin, Anne d’Aquino ’20 PhD, who would defend her biology doctoral thesis a month later. Andrea’s defense was followed by a short celebration that wrapped up just before midnight. The next morning, the d’Aquino sisters woke up at 3 a.m. to make the trip to Stateville. Anne had been tutoring at the prison all quarter — and teaching a biology minicourse in a Cook County Jail program (which she co-coordinates) — while preparing to teach biology at Stateville the following quarter.

Andrea had been coming weekly to teach chemistry with her co-teacher Steven Swick ’20 PhD, who would also defend his chemistry doctoral thesis in the fall.

“Some of the students hadn’t taken chemistry in a very long time,” says Andrea, “so Steven and I worked together to design a course that made chemistry approachable. In their final papers, the students took a creative approach — explaining the chemistry of the world around them in letters addressed to their mothers, cousins

and kids.”

The d’Aquino sisters and Swick are headed to Stanford University for postdoctoral positions this year. They are just three graduate students whose experiences at Stateville have had a profound impact on their relationships with their disciplines and with teaching.

“NPEP has a positive impact on everyone involved — the Stateville and Evanston students who are expanding their worldview and the graduate students and professors who are becoming better teachers,” says former Northwestern provost Jonathan Holloway. “When I look at how transformational the program has been for the Northwestern community, I’m inspired to think it has the potential to be a beacon in the world of prison education in this nation.”

New Northwestern program transforms the lives of inmates, students and faculty